INTRODUCTION

Barbara Fuchs

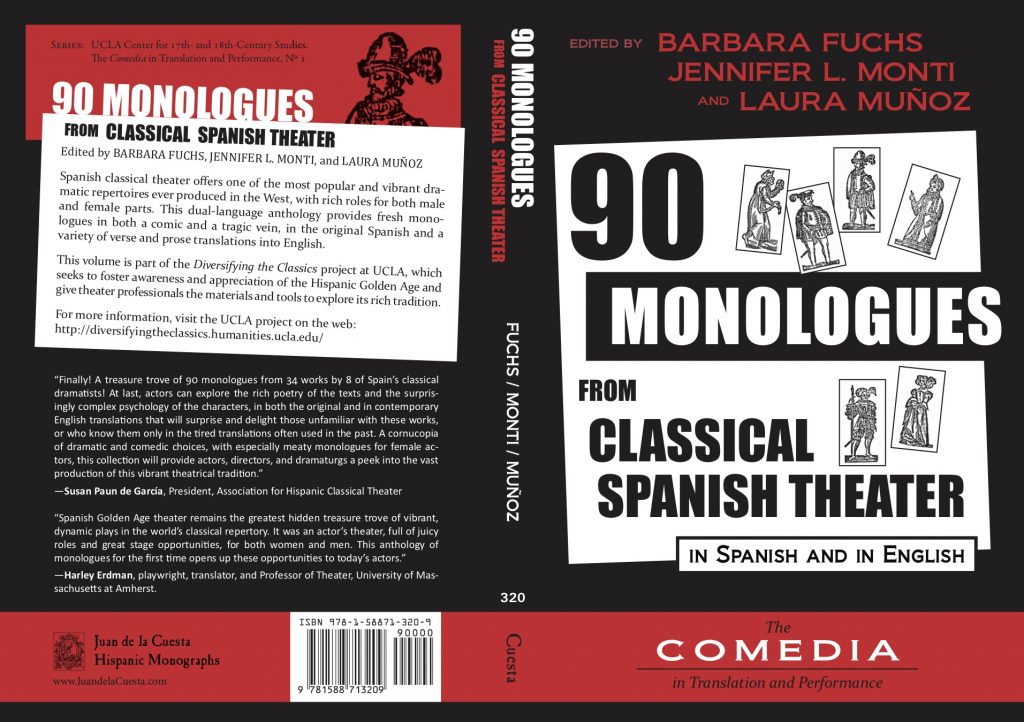

Spanish classical theater offers one of the most popular and vibrant dramatic repertoires ever produced in the West, and deserves to be far better known in the English-speaking world. This dual-language anthology is intended to provide you with wonderful audition monologues, to be sure, but also to spark your interest in the plays included here and the broader canon that they represent. We offer the original Spanish as well as a range of translations in verse and prose, to give a sense of the tremendous variety available. Our volume is part of the Diversifying the Classics project at UCLA, which seeks to foster awareness and appreciation of Hispanic classical theater and to give theater professionals the materials and tools to explore its rich tradition.We hope that you will enjoy the great variety of characters and situations represented here, and that you will read further.

WHAT WAS THE COMEDIA?

During the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the comedia (as all the plays, and not just comic ones, are known) became a vibrant and hugely popular form. As Madrid grew into the powerful capital of Spain’s global empire, theater grew with it, becoming its most important cultural production. In simple, open-air theaters across Iberia and the Americas, theater flourished.

The comedia is centrally concerned with how persons are fashioned and represented: from sexuality to class to political loyalty, appearances matter. In various ways, the plays explore what it means to be a modern subject, whether that involves resisting the excesses of rapacious noblemen, scheming to marry for love, or trying on the fashionable identities that the big city offers. As a corpus, the comedia effectively makes the point that modernity is itself theatrical.

Hundreds of plays from this “Golden Age” of drama have survived, over four hundred by the great Lope de Vega alone. The incredible demand for new plays—most of which had very short runs—meant that Lope and his contemporaries produced a massive oeuvre, based on a wide range of popular, literary, and historical sources. Our anthology includes plays by the authors most frequently produced—Lope, Calderón de la Barca, Tirso de Molina, Alarcón—as well as those such as Guillén de Castro, who deserve a wider audience. Women, too, wrote plays, in Spain as in the Americas: in Mexico, the learned nun and protofeminist Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz tried her hand at the comedia with wonderful results.

The corpus includes plays about distant times and places—ancient Rome, or the exoticized far reaches of Europe—as well as about current events. Many of the most famous and heroic dramas—Fuente Ovejuna the best known among them—idealize virtuous peasants who challenge abusive authority figures. Others—The Dog in the Manger, The Force of Habit, Don Gil of the Green Breeches—cast a much more skeptical eye on the pieties of their own society. Urbane and witty, they emphasize the flexibility and constructedness of social norms in the burgeoning city. Whether set in familiar or faraway places, the comedia stages a realistic world, full of passions and pleasures easily recognizable to its audience.

AN AFTERNOON AT THE CORRAL

Theater was the event in early modern Madrid—the place to see and be seen. With plays designed to please a broad audience, the comedia functioned as the first real commercial theater, and made the fortunes of Lope and other successful playwrights. Flexible and topical, the plays appealed to a wide range of people of both sexes and of every class, from the nobles who sat in the balconies to the rowdy mosqueteros (groundlings) on benches in the patio of the corrales, as the theaters were known.

An afternoon at the theater would have included song and dance, and a number of short performances in addition to the main play. The monologues in this anthology are all from full-length plays; they would have shared the stage with interludes, dances, dramatic prologues, and other short forms. A guitarist would likely have played throughout, with occasional songs during the plays.

Backdrops and props were minimal, although the corrales gradually added trapdoors and other special effects, useful for characters disappearing into the underworld and other such spectacular moments. In general, a balcony above and a series of entrances were the key elements to the staging.

HOW TO WRITE A SUCCESSFUL PLAY

In his witty, tongue-in-cheek manifesto, the New Art of Making Plays in Our Time (1609), Lope argued that literary rules were not important—instead, playwrights should focus on what worked, and what kept audiences engaged: plots of love and honor, strong subplots, cross-dressing whenever possible.

In the original Spanish, almost all the plays are in verse, with a variety of metrical forms used to signal different moods and levels of speech. The lively verse samples liberally from the Petrarchan tradition of love lyrics, as well as from popular ballads and songs. Compact and lively, the plays typically include at least one plot and subplot over three acts and around 3000 verses. The action comes fast and furious, and the pacing is intense. In many comedias, upper-class protagonists rely heavily on their comic sidekick, the gracioso, who often plays an outsize role in the action. In others, as noted, peasants are granted tremendous dignity and agency.

Although Lope clearly found a winning formula and exploited it magnificently, the plays that he and his contemporaries wrote are anything but formulaic. Instead, they run the gamut from tragic to comic with everything in between. Most importantly, they succeed marvelously in pleasing audiences, which was always the central goal.

CALLING ALL ACTRESSES!

Actresses were hugely important within the comedia, divas in their own time, and the fabulous roles written for their particular abilities offer untold possibilities for modern practitioners. In fact, one of the most exciting features of the corpus, especially for actors accustomed to the Shakespearean canon, is the wonderful variety of female roles. Unlike in England, moralists in Spain generally decided that having women on stage, though scandalous, was still preferable to the alternative of having boys play women. In Spain, women played the female roles, and this naturally impacted the plays and the roles that were written for them. Sometimes actresses even dressed up as men, since the availability of women in no way diminished the appeal of cross-dressing plots. Thus gender, like class, becomes part of the structure that the comedia examines and dismantles, offering a powerful reflection on how we come to be who we are.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank our colleagues in the UCLA Working Group on the Comedia in Translation and Performance for their invaluable assistance with this project, from its earliest stages. We owe a huge debt to Dakin Matthews for making his wonderful translations, both published and in progress, available to us, as well as for writing such a thoughtful prologue to our volume. His work as translator, actor, and director is a real inspiration to us. We are also grateful to the many scholars and practitioners who offered suggestions for monologues to include in the anthology—if we’ve missed your favorite, do let us know, and we’ll include it in the next installment. Susana Schuarzberg generously read over the entire manuscript, in both languages. We are so very grateful for her assistance.